Charlotte Brontë  Jane Eyre

Jane Eyre

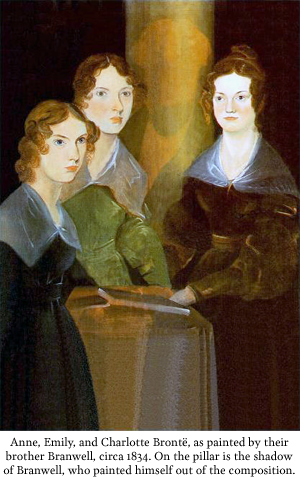

Charlotte Brontë was born on April 21, 1816, in the village of Thornton in Yorkshire, England, the third of six children born to Maria Branwell and Patrick Brontë, an Irish Anglican clergyman and poet. Charlotte was the third, and youngest, daughter in the family at the time she was born, but would be the eldest of the children to survive into adulthood. At the age of four, her father moved the family—now including Charlotte’s two older sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, and her younger siblings, Patrick (known as “Branwell”), Emily, and Anne—from Thornton to nearby Haworth, a rustic village in Yorkshire, to assume the post of perpetual curate at the local parsonage.

Charlotte Brontë was born on April 21, 1816, in the village of Thornton in Yorkshire, England, the third of six children born to Maria Branwell and Patrick Brontë, an Irish Anglican clergyman and poet. Charlotte was the third, and youngest, daughter in the family at the time she was born, but would be the eldest of the children to survive into adulthood. At the age of four, her father moved the family—now including Charlotte’s two older sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, and her younger siblings, Patrick (known as “Branwell”), Emily, and Anne—from Thornton to nearby Haworth, a rustic village in Yorkshire, to assume the post of perpetual curate at the local parsonage.

The hamlet, situated among the picturesque yet isolated North England moors, was typical of small towns of the era, lacking amenities like sewers and a reliably clean water supply, which inevitably led to outbreaks of disease. Just a year after moving to Haworth, on September 15, 1821, Charlotte’s mother, Maria, died after a long battle with cancer. Maria’s sister, Elizabeth, known to the children as “Aunt Branwell,” moved in with the family to help raise Charlotte, her four sisters, and brother Branwell. Despite the loss of their mother, the children thrived in their small-town environment, playing on the moors that surrounded the parsonage, reading voraciously from their father’s library, and making up stories and games with one another. The eldest daughter, Maria, took an influential role in the family after her mother’s death, reading to her father and siblings from the pages of Blackwood’s Magazine, directing her siblings in putting on plays, and encouraging their budding literary interests.

In August 1824, Maria and her sisters Elizabeth, Charlotte, and Emily were sent to the Clergy Daughter’s School in Cowan Bridge, Lancashire. The boarding school’s austere conditions were a drastic change of environment for the girls, and the two eldest, Maria and Elizabeth, contracted tuberculosis while there, in part due to the school’s harsh treatment and unsanitary practices. Informed of Maria’s illness in February 1825, Reverend Brontë immediately brought her back home, where she died in early May. He quickly removed Elizabeth, Charlotte, and Emily from the school, but Elizabeth was already ill and died at home in June. Charlotte would later incorporate some of the details from her experience at Cowan Bridge into the Lowood School, which figures so prominently in Jane Eyre.

Back home in Haworth, Charlotte was suddenly the oldest of a very creative and insular group of children. They invented games, did needlework and embroidery, and entertained each other on the piano and with stories around the hearth at the parsonage, with Charlotte now taking on the role her eldest sister Maria had once played. In June 1826, when Branwell received the gift of some wooden soldiers from his father, all four siblings claimed a share of the toys. Each child picked a favorite soldier, giving them names and constructing stories and adventures around each character. Branwell and Charlotte created for theirs the imaginary country of “Angria.” And Emily and Anne began writing poems and stories about their invented island world of “Gondal,” told in their characters’ voices. Some of the earliest examples of these were written in tiny handmade books in almost microscopic handwriting, as if the miniature soldiers had penned the stories themselves (some of these manuscripts still exist at the British Museum). In short, the four siblings were busily preparing to become the literary and creative artists that all of them would later be.

Charlotte returned to boarding school in 1831 at Roe Head School, near Mirfield (about eighteen miles from Haworth). She studied at Roe Head until 1832, when she returned home to tutor her younger sisters. In 1833 she wrote her first novella, The Green Dwarf, under the imposing pen name of Lord Charles Albert Florian Wellesley, an anonymity commonly employed by women authors of the day, and which Charlotte would continue, under a less unwieldy moniker, in her publishing career. At the age of nineteen, in 1835, Charlotte returned to Roe Head as a teacher, where her sisters enrolled as students the following year. She still longed to write for a living and chafed at the tedious aspects of teaching. In 1836 she sought the advice of Robert Southey, England’s poet laureate, to whom she enclosed several of her poems. His response was less than helpful. “Literature,” he informed her,

cannot be the business of a woman’s life: & it ought not to be. The more she is engaged in her proper duties, the less leisure she will have for it, even as an accomplishment & a recreation. To those duties you have not yet been called, & when you are you will be less eager for celebrity.

She kept Southey’s letter for the rest of her life—and her subsequent prodigious output of verse and other writings can leave little doubt as to what she thought of the old man’s advice.

Still, Charlotte taught at Roe Head for three years before taking the first of several governess positions in 1839. She worked for two different families over the next three years but was ill-suited to the role, and both situations ended badly. She was trying, unsuccessfully, to reconcile her need to express herself as a writer with the cruel necessity of earning a living.

In 1842 Charlotte and Emily traveled Brussels to study and work as instructors at the Pensionnat Héger under the tutelage of Constantin Héger. There they learned French and German and studied literature with the goal of starting their own school someday. They returned to Haworth soon after, however, when their Aunt Branwell died in October. Charlotte returned alone to Brussels in January 1843, but was unhappy there, homesick and in love with the married headmaster, Héger, whom she regarded as “my literature master . . . the only master that I have ever had.” When Madame Héger tried to distance her husband from his young student, Charlotte withdrew from the school. She returned to Haworth in January 1844, her time in Brussels giving her experience that would provide, among other things, material for her novels The Professor and Villette.

After Charlotte and her sisters’ attempt to start a school in Haworth foundered, Charlotte fell into a year-long funk, which only subsided in the fall of 1845 when she came across and read her sister Emily’s notebook (as sisters sometimes will). Emily had been copying her original poems into the notebook and at first was not at all pleased by Charlotte’s intrusion. Finding her sister’s poetry to be uncommonly good, and unique among women poets, Charlotte won Emily over to the idea of publishing her poetry, along with selections by herself and their sister Anne. Agreeing to use the pseudonyms Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, they printed the collection at their own expense through the publisher Aylott and Jones in 1846. In choosing the ambiguous pen names, the three kept their initials while obscuring their gender—an attempt to prevent their sex from being the basis upon which their work would be judged. Though Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell did receive some favorable notices, the book did not sell—in fact, in the first year it garnered more reviews (three) than sales (two).

But Charlotte used the occasion of her literary debut and slight critical success to pave the way for her and her sisters’ other literary works, namely the novels they had each been working on. Charlotte attempted to sell her novel, The Professor, but met with nine separate rejections. It was only with the tenth that a glimmer of hope emerged. The publisher, Smith, Elder & Co., also declined The Professor but did express interest in other works that “Currer Bell” might be working on, and which were long enough to be published in three volumes. Charlotte spent the next two weeks feverishly finishing her other novel, Jane Eyre, and submitted the manuscript to the publisher in August 1847. Six weeks later, the novel was released (in three volumes, naturally) and enjoyed instant critical and commercial success, necessitating second and third editions of the book to be produced within six months. The simultaneous release and success of Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey in December 1847 drew more attention to the literary “Bells” and questions as to their identity and gender, as well as about whether they were three authors or one.

By September 1848, Charlotte was already hard at work on her next novel, Shirley, when the first of three tragedies struck the Brontë family. Her younger brother, Branwell, who had never achieved his artistic ambitions as a painter or writer and had been disgraced after an affair with his employer’s wife, died of chronic bronchitis and malnutrition exacerbated by heavy drinking and an opium addiction. Emily soon after took ill with tuberculosis, refused treatment, and died in December 1847. Then Anne, after a prolonged battle against the same disease, died while with Charlotte in the seaside resort of Scarborough in May 1849. Other than poems composed after the death of her two remaining siblings, Charlotte could not bring herself to write. Among the few things she wrote during this period were these lines from her poem, “On the Death of Anne Brontë”:

There’s little joy in life for me,

And little terror in the grave;

I’ve lived the parting hour to see

Of one I would have died to save.

Charlotte eventually returned to her unfinished novel and published Shirley in October 1849. Although a distinctly different work from Jane Eyre—a third-person narrative, which was less romantic and perhaps less shocking than her debut—it still sold well, although with mixed reviews. After the success of her second novel, Charlotte’s publisher convinced her to come to London on occasion, where she publicly revealed her true identity and was welcomed into literary society. She would befriend G.H. Lewes, Elizabeth Gaskell (her eventual biographer), and her idol, William Makepeace Thackeray, among others, but would never be entirely comfortable in such cosmopolitan company. Naturally timid and extremely near-sighted, Charlotte was always more in her element at home, despite the tragedies that had by then ravaged her family. In 1851 she edited a new edition of Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey, adding an introductory biographical sketch of her sisters.

While still living in Haworth and preparing her next novel, Villette, for publication, Charlotte received a proposal of marriage from Arthur Bell Nicholls, her father’s curate. Arthur had long admired Charlotte, but she felt unsure and her father disapproved of the match, at least in part due to her suitor’s relative poverty. She turned down his offer at first but continued to correspond with Arthur while Elizabeth Gaskell urged her to reconsider and worked to improve his financial situation (she approved of the match and of marriage, in general). That same year, 1853, Charlotte published Villette, the first-person account of a young woman, Lucy Snowe, who leaves England to teach at a boarding school in the fictional town of Villette. Feeling isolated in a foreign culture, with an unfamiliar language and the Catholic religion, Lucy falls in love with a man she cannot marry. Villette, like Shirley, would not achieve the kind of success Jane Eyre had, but did do well in its own right and is still widely regarded to this day.

After months of courtship, Charlotte reconsidered Arthur’s proposal and, in January 1854, accepted. With the approval of her father, they married in June and honeymooned for a month in the south of Ireland. Charlotte became pregnant by the fall, but soon became severely ill from acute morning sickness, which caused near-constant nausea, faintness, and dehydration. Her short but happy marriage ended when she died with her unborn child on March 31, 1855. (Another possible cause of her death could have been typhus, which she may have contracted from a servant who had died of the disease prior to Charlotte’s passing.) Charlotte Brontë was buried in the family vault in the Church of St. Michael and All Angels in Haworth alongside her mother, brother Branwell, and sisters Maria, Elizabeth, and Emily (Anne was laid to rest in Scarborough). She had been at work on an unfinished novel at the time of her death (Emma), and her first, unpublished novel, The Professor, was released posthumously in 1857. A stone tablet, erected in 1939, commemorates Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey, placed on the wall beside the memorial sculpture of William Shakespeare.

Published Works of the Brontë Sisters

- Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell (1846)

by Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë - Jane Eyre (1847) by Charlotte Brontë

- Wuthering Heights (1847) by Emily Brontë

- Agnes Grey (1847) by Anne Brontë

- The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) by Anne Brontë

- Shirley (1849) by Charlotte Brontë

- Villette (1853) by Charlotte Brontë

- The Professor (1857, posthumous) by Charlotte Brontë

- Emma (1860, unfinished, posthumously published in

Cornhill Magazine) by Charlotte Brontë

- Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell (1846)