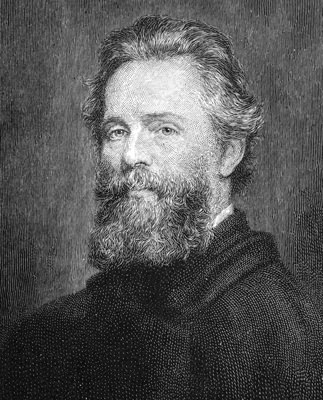

Herman Melville  Moby-Dick

Moby-Dick

Herman Melville was born on August 1, 1819, in New York City, the third of eight children born to Allan Melville (spelled “Melvill” during his life) and Maria Gansevoort Melville. The product of a well-established, prosperous family—both of Melville’s grandfathers were heroes of the Revolutionary War and his father was a merchant and importer of French dry goods—Melville’s childhood in Manhattan was pampered and privileged, though not without hardship. Having survived scarlet fever in 1826, Melville struggled in school at a young age before showing signs of academic promise at the New York Male High School he and his older brother Gansevoort attended until 1829, when they transferred to Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School. During this time, the family’s opulent lifestyle was due in no small part to the fact that Allan Melvill liked to live beyond his means, borrowing money from both his father and mother-in-law until he was $20,000 in debt to them by 1830, at the same time his importing business collapsed.

Herman Melville was born on August 1, 1819, in New York City, the third of eight children born to Allan Melville (spelled “Melvill” during his life) and Maria Gansevoort Melville. The product of a well-established, prosperous family—both of Melville’s grandfathers were heroes of the Revolutionary War and his father was a merchant and importer of French dry goods—Melville’s childhood in Manhattan was pampered and privileged, though not without hardship. Having survived scarlet fever in 1826, Melville struggled in school at a young age before showing signs of academic promise at the New York Male High School he and his older brother Gansevoort attended until 1829, when they transferred to Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School. During this time, the family’s opulent lifestyle was due in no small part to the fact that Allan Melvill liked to live beyond his means, borrowing money from both his father and mother-in-law until he was $20,000 in debt to them by 1830, at the same time his importing business collapsed.

In an attempt to improve his finances, Melville’s father moved the family to Albany, where he went into the fur business. Melville attended the Albany Academy for a year, but the expense proved too much, and he had to quit in October 1831. Three months later, after an illness brought on by a long trek home from New York in sub-zero weather, Allan Melvill died on January 28, 1832, leaving the family in desperate straits. At the age of twelve, young Herman Melville found work as a clerk at the New York State Bank with the help of his maternal uncle Peter, who was one of the bank’s directors. Melville worked there two years before being hired by his older brother Gansevoort to staff the cap and fur store he’d taken over from their father. Melville was able to resume his studies, first at Albany Classical School and then Albany Academy until 1837. That year, an economic crisis forced Gansevoort out of business and into law school in New York City, while Melville found a teaching job at Sikes District School outside of Lenox, Massachusetts. The next year, Melville’s mother moved the family to a rented house in Lansingburgh (later Troy), New York, as rents in Albany had become too expensive. Melville joined the family there, took a course in surveying and engineering but failed to get a job in the field, and published his first letters in the Albany Microscope and then his first essay in the Democratic Press and Lansingburgh Advertiser.

A letter from Gansevoort to Melville on May 31, 1839, would prove pivotal for the aimless nineteen-year-old. Gansevoort wrote from New York that he thought Herman could get hired aboard a whaler or merchant vessel there, and Melville jumped at the chance, signing on as a green hand on the merchant ship St. Lawrence the next day. After sailing to Liverpool and returning to New York in October, Melville taught for a term in Greenbush, New York, and then headed west with a friend to Galena, Illinois, to visit his father’s brother Thomas and look for work. But the next year, Melville and Gansevoort traveled north to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where Herman signed on to work on a whaler, the Acushnet, which set sail on January 3, 1841. Working as a green hand (the lowest level of crew member) once again, Melville slept with twenty other sailors in the ship’s forecastle as they sailed around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America and cruised the South Pacific hunting and butchering sperm whales, storing the animals’ oil in barrels in the ship’s hold.

After eighteen months, in June 1842, the Acushnet anchored in the Marquesas Islands, and Melville and a crewmate jumped ship and fled to the mountains around the Taipi Valley. In August, Melville joined the crew of the Lucy Ann, bound for Tahiti, where he took part in a mutiny and was held in Tahiti’s “Calabooza Beretanee,” the English jail that was little more than a grass hut overseen by an easygoing Tahitian called Captain Bob. In October, Melville and a shipmate rowed over to the neighboring island of Moorea (then known as Eimeo) and spent a month there as a beachcomber (omoo in Tahitian). In November, he signed on with another whaler out of Nantucket, the Charles & Henry, for six months and was let off in Lahaina on Maui in the Hawaiian Islands. There he worked odd jobs for four months before joining the U.S. Navy as an ordinary seaman on the frigate USS United States, sailing for thirteen months through the South Pacific, back around Cape Horn, and arriving in Boston in October 1844, where he was discharged from the Navy.

The romantic, adventurous tales that he spun out of his three-and-a-half-year sojourn halfway around the world and back again convinced his family and friends that he should write them down. The result was Melville’s first book, Typee, which recounted his adventures in the Marquesas with a good deal of artistic license. Finished in the summer of 1845 and published first in London in February 1846 and then in March in the U.S., the book became an instant bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic. The book made Melville a minor celebrity and first brought him to the attention of Nathaniel Hawthorne, who reviewed it favorably in the Salem Advertiser. Typee also enabled Melville to publish its successful sequel, Omoo, which was released in March 1847 simultaneously in Great Britain and the U.S. and which detailed his time in Tahiti and Moorea.

In August 1847 Melville married Elizabeth Knapp Shaw, the daughter of Lemuel Shaw, the chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court and an old friend of Melville’s father. The couple honeymooned in Canada and settled in a home on Fourth Avenue in Manhattan. They would have four children together over the next eight years, two boys (Malcolm and Stanwix) and two girls (Elizabeth and Frances).

Melville continued writing, contributing to literary journals and publishing three more novels—Mardi (1848), Redburn (1849), and White-Jacket (1850)—to varying, but generally less enthusiastic, receptions. In 1850 he befriended the author Nathaniel Hawthorne, along with other notable literary figures from New York and Boston, who gathered in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in the summer for picnics, parties, and dinners. Melville bought a house there that fall which he dubbed “Arrowhead” while working on his most ambitious book to date, a tale inspired by the real-life albino whale Mocha Dick and the sinking of the whaler the Essex. It would incorporate his own experiences aboard whaling ships as well as his literary influences, from the King James Bible to Shakespeare.

Dedicated to Hawthorne, The Whale was first published in London in October 1851 by Richard Bentley to mixed reviews, and then a month later in New York by Harper & Brothers under its definitive title, Moby-Dick. Hundreds of mostly minor differences exist between the two editions thanks to its censorious London publisher, but the most significant was the fate of the Epilogue. Excluded from the British version for what reason is now lost to history, many of the initial reviews faulted the novel for being told by the presumably drowned narrator, Ishmael. Some of the negative British criticisms followed the book across the pond, despite the presence of the Epilogue in the American edition, which explains Ishmael’s survival and rescue.

The tepid response to Moby-Dick—it sold about 3,200 copies during his lifetime—was a portent of Melville’s struggle to regain the popular and critical success he enjoyed earlier in his career. Over the next six years, he would publish three more novels, Pierre (1852), Israel Potter (1855), and The Confidence-Man (1857); a collection of stories, Piazza Tales (1856), which included “Bartleby, the Srivener”; and one unpublished (now lost) novel, Isle of the Cross (1853). Critical reception ranged from bewildered to hostile, while the public reaction remained more or less indifferent.

The Confidence-Man would be Melville’s last published novel, released while he was making a seven-month tour of Europe and the Holy Land. Upon his return, he attempted to restore his finances by embarking on a series of lecture tours from late 1857 to 1860. Although lucrative for many authors, these were received by audiences with no more enthusiasm than his recent fiction. Turning to poetry during and after these years as a failed novelist, Melville continued to travel, sailing with his younger brother Thomas around Cape Horn to California in 1860 and visiting Virginia battlefields during the Civil War in 1864. He published a collection of poems, Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War, in 1866, which was ignored by critics and readers alike.

In 1866 Melville’s wife and her relatives secured a job for him as a customs inspector in New York City, a job he would hold for the next nineteen years. In 1867 Melville’s eldest son, Malcolm, died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound—whether intentional or not is unknown. Mostly forgotten as an author in his later years, Melville continued to write, composing an eighteen thousand–line epic poem titled Clarel: A Poem and a Pilgrimage, about a young divinity student’s journey to Jerusalem, of which the author printed 350 copies.

Melville retired from the customs house in 1885. The family endured tragedy again in early 1886, when Melville’s younger son, Stanwix, died in San Francisco at the age of thirty-six. In the last years of his life, Melville printed two more collections of his poetry, John Marr and Other Sailors (1888) and Timoleon (1891), in print runs of twenty-five copies for friends and relatives. One of the poems from John Marr inspired Melville to return to fiction and create the unfinished novella Billy Budd. Melville died of “cardiac dilation” on September 28, 1891, at the age of seventy-two, at his home in New York.

Although his widow edited and added notes to his last, unfinished work, Billy Budd remained hidden away until 1919, when Melville’s first biographer, Raymond Weaver, discovered it during his research. The year 1917 had marked a renewed interest in and reappraisal of Melville’s work, after the critic and biographer Carl Van Doren wrote an appreciation of Melville for a survey of American literature. Weaver’s biography, Herman Melville: Mariner and Mystic, came out in 1921, and Melville’s legacy blossomed in ways that he could only have dreamed of during his lifetime. In 1924 Weaver published the full text of Melville’s Billy Budd, Sailor to immediate critical and popular success. In time Moby-Dick would become the embodiment of the great American novel, perhaps only rivaled by The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Great Gatsby in any serious discussion of American literature up to the present day. D.H. Lawrence called Moby-Dick “one of the strangest and most wonderful books in the world.” Melville’s poetry would, in the late twentieth century, receive a similar reexamination by scholars, many of whom now consider his verse in a league with Walt Whitman’s and Emily Dickinson’s.

Mostly dismissed by readers and critics by the time he was forty, all of Herman Melville’s major works remain in print to this day, and he is rightly considered one of the titans of American literature.