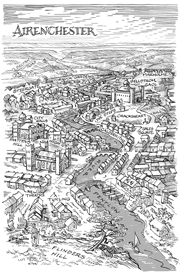

MR. GRAINGER continued on foot, descending from Haught into Turling and the low town. Many carriages rolled abroad, as the best of Airenchester took their pleasure, for Lady Stepney's was not the only place to call tonight. Link-boys scuttled through the streets with their lanterns to light the way for well-dressed gentlemen. Grainger's mood improved as he got in among the scrawl of streets and dim courts clustered in genteel chaos nigh on the river and in the daylight shadow of the Cathedral spire. He came into a small, dark square, where old-fashioned houses with steep roofs and carved gables leaned against each other. All was quiet. He searched about by the thin light of the half-moon, and gathered up a handful of fragments of a shattered cobblestone. He stared up, counting audibly under his breath, until he found the one high window he sought. Then he took a stone in hand and lofted it against the glass. The stone struck the pane and rattled away, but the noise did not disturb the repose of the square. Grainger selected another shard heavier than before, aimed, and loosed it at the same target. He was testing a third missile when the little window opened a fraction. "Who's that?" cried a voice. "William, are you asleep?" "Not a bit. I happen to be standing at my window, conversing with a madman." Grainger hurled another pebble, which clattered against the wall. The window was thrown open, and the head of Mr. William Quillby appeared, almost filling the frame. Quillby was near on Grainger's age, a clergyman's son encumbered by education and no fortune. He was, by profession, a scribbler and taker of notes, and to this end a journalist who followed society and the courts. On occasion he intervened sensibly in fractious coffeehouse debates, in consequence of which he was known to quietly entertain Views not always to the credit of authority, and on one side or another of the latest cause he and Grainger had first marked their acquaintance. His good humour well matched Mr. Grainger's restless moods. William had a mass of brown hair, perpetually disordered and now tousled by sleep; a broad, honest face; and guileless brown eyes. He wore his nightshirt. "For God's sake, stop that!" he hissed. "Get up, William!" Another flying stone clipped the frame. "I am up! You'll wake the whole house!" Mr. Quillby lodged in the compact top-room of a respectable (if limited) establishment. "What?" "I said you'll wake the whole—no more stones, if you please!" "I just wanted to see if you were awake." Mr. Quillby returned to the window and said resignedly: "Evidently I am. Evidently, I have no better way to spend my evenings but to wait on lunatics flinging masonry about." "Excellent fellow!" For the first time this night, his coolness and airy manner were discarded, and Grainger grinned up at the open window. "Let's go out." "You have been out. To Lady Stepney's, I assume." "I have been stifled and overheated; I have been condescended to; I have been courted and expected to pay court, in the name of good form; in short, I have been fatally bored—but I have not been out." "Are you drunk?" asked Quillby. "No, no. Not in the least. I am merely a little short of the high mark of sobriety." "What time is it?" Mr. Quillby did not soften his suspicions. "It is but midnight." "I thought it rang two." "So it did. William, come down, I implore you. You are the only worthy fellow in this town. The only fellow who is not a slave to good form." "I must turn in some work tomorrow. I have in mind a piece pointing out the most grievous abuses of the clothmakers—" "Tomorrow, good! Work on it tomorrow. Admirable. Come down to the Saracen and tell me all." "I was asleep," returned Mr. Quillby, becoming querulous. "A good glass of Rhenish will settle you for writing," declared Mr. Grainger. The last chip in his hand sprang at the casement. "If you only stop that, I shall be down presently," said Mr. Quillby, resigned. "William, you are the best of friends," said Grainger, clasping his empty hands behind his back. • • •

CLUSTERED BELOW the sheer face of Cracksheart Hill, The Steps lay within sight of the Bellstrom Gaol. There was no straight path from The Steps to the gaol, though it seemed to command everything below, for at the highest point of that district were nothing but hard cliffs and weathered reaches of stony wall, reaching to the base of the castle. A prisoner forlorn in the lowest cells might stare out through hard bars onto the top of The Steps and behold a tumbling, toppling pile of steep little roofs, missing and broken tiles and slates, crooked, narrow chimneys set all askew, and the winding, constricted stairs and pinched lanes that made up that quarter. But the eye could not see the noisome drains and fetid puddles, nor apprehend the stench of rags or smouldering coal fires, or the foul air of close human habitation. A mass of rickety hovels, slumping walls, makeshift doors, cracked and winding stairs leading one to another in no order, uneven yards, and scavenged lumber was The Steps. Closer to the river than the gaol, at the top of a coiling set of crumbling stairs, lay Porlock Yard, a frozen, muddy square, four slumping walls of blind windows and descending moss. In one corner, close to the ground, stood a door somewhat stronger than most, and behind it a dark lodging-room. Not entirely dark: in a little stove the coals were burning down to feathers of ash, and their glimmerings fell upon the grate. On a chair by an uneven table sat the sturdy figure of a woman, dozing, with a bundle in her lap that could only be a small child wrapped against the chill. Underneath the table, indistinctly seen, were three or four small heaps of clothes and blankets, twitching and shifting occasionally, and in the farthest corner of the room, on a low bed, was another figure beneath a heap of covers. A far bell chimed. There was little silence to be had in Porlock Yard. At all hours there could be heard heavy footfalls on the rattling stairs, the shuffle of bodies stretched on those same stairs, the groan of timbers, the bellows of men and the shrieks of women, and the cries of children. The little room was uneasy with breathing. Another woman, more slender than the first, nodded and dozed on a three-legged stool by the stove. Every movement in the yard drew her out of rest. The person on the low wooden bed coughed, stirred, muttered, coughed again, and turned all around. A dark head rose. "Cassie, is he back yet?" The younger woman drowsing on the stool shook herself. "No, Father." "Damn the boy. Where's he gone?" "I don't know, Father." "I think you do." The girl did not reply. The bed creaked as the man shifted. "Fetch a light, child." The girl rose, as softly as she could, and rummaged along a thin mantelpiece for a rushlight. She took it to the stove, leaning forward to open the grate. For a moment, the faint orange glow touched her face. It was a youthful face, though it had known want, weariness, and fear. The grey eyes were bright and clear; the line of brow and cheek strong, though haunted now by thought. From under the shawl some strands of the lightest brown hair escaped, which caught, by the dying embers, stray touches of red and gold. She fired the wick from the ashes and brought it back to the table. The heavy figure in the deep chair was roused, raised herself, and the child in her lap mouthed a complaint. The woman's face was thickened by age and veined and coarsened by labour and harsh wear. It had been handsome once, and the hair, with more red in it than her daughter's, was threaded with strands of white. "What is it?" said the woman. "Is he back?" "Not back," replied her daughter. The stronger glow revealed also the head of her father, propped on one hand and an elbow, above a mass of worn covers and clean rags. The head was shaggy, seamed, and weathered. Along one side gleamed an old scar, got from a bayonet. "You know where he's gone. The boy tells you everything," accused Silas Redruth. "I'm sure I don't." The two dark eyes narrowed on her. "What a thing it is, to be an honest man with two defiant children! If you don't know, you guess." "Leave the girl be!" soothed Meg Redruth, hushing the child, who had grown restive in her grasp. "Mark my words: she knows!" The girl sat again and lowered her head. "It may be he is at the Saracen. He thought to go there earlier and—" "The Saracen!" crowed her father. "Bad company. Bad company. Plots and schemes are made at the Saracen. Half the evil in this city, mark you. What sort of thing is it for an honest man's son to be at the Saracen? What time is it?" "It's late, Father." "Fetch him back." "Father—" "Silas!" The whole mass, man and covers, rose, and one foot only touched the ground, showing an absence from the knee where the other should be. "Are you too proud, girl, to obey your father? Should I go myself? Should a father wait upon his own son to say, 'By-your-leave,' and, 'An-it-should-please-you,' to have his own boy back home at a respectable hour? Fetch him back, I say. Will I have two disobedient children?" "No, Father." "Fetch him back. Here, where's my boot, my staff?" "Silas. My girl is a decent girl. Think on the hour, you old fool." "'Tis the hour when an honest man expects his kin to be under his roof." The children under the table were alerted and called sleepily to their mother, who continued hushing the little one on her knee and had no more chance to argue. The little lodging broke into a tumult of voices and complaint. The girl stood. She was still dressed, for the room remained dull and cold even a few steps from the smouldering stove. "I will go," she said. "Do not stir yourselves more." Cassie waited until the old man had reclined on the bed, picking at the blankets and arranging them around his throat. The other children had to be quieted and persuaded to sleep again. Then she bent over the rushlight and extinguished its meagre flame. She tugged her mother's shawl closer over the seated woman and wrapped it tightly about the baby as well, and then she went to the door, undid the bolts, and pulled it wide. For a moment the frost, the night, and the cold colour of the few scattered stars streamed in at the doorway. She peered into the uneasy silence of Porlock Yard. "Bring him quick, mind. Don't linger!" urged Mrs. Redruth in a low whisper. "You are a good girl, Cassie," said her father, relenting. The girl shivered, drew her shawl tighter over her head, and stepped out into the fast wasting night. • • •

|

Top Five Books, LLC,

is a Chicago-based independent publisher dedicated to publishing only the finest fiction, timeless classics, and select nonfiction.

is a Chicago-based independent publisher dedicated to publishing only the finest fiction, timeless classics, and select nonfiction.

© Top Five Books, LLC. All rights reserved.