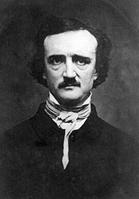

Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe was born on January 19, 1809, in Boston, the second of three children born to actors David Poe Jr. and Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins. His parents weren’t around long, however. A year after giving birth to Edgar’s younger sister, Rosalie, in 1810, Elizabeth took ill during the run of a play in Richmond, Virginia, and died of “consumption” (tuberculosis) on December 8, 1811. David Poe, a quick-tempered alcoholic who was apparently not much of an actor, had reportedly deserted the family sometime in 1809. Within a few days after his estranged wife’s passing, he died, also possibly of tuberculosis, while in Norfolk, Virginia.

Edgar Allan Poe was born on January 19, 1809, in Boston, the second of three children born to actors David Poe Jr. and Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins. His parents weren’t around long, however. A year after giving birth to Edgar’s younger sister, Rosalie, in 1810, Elizabeth took ill during the run of a play in Richmond, Virginia, and died of “consumption” (tuberculosis) on December 8, 1811. David Poe, a quick-tempered alcoholic who was apparently not much of an actor, had reportedly deserted the family sometime in 1809. Within a few days after his estranged wife’s passing, he died, also possibly of tuberculosis, while in Norfolk, Virginia.

So, by the end of 1811, the not-yet-three-year-old Edgar Poe, his older brother William Henry Leonard (called Henry), and baby sister Rosalie were orphans. Henry was taken in by his paternal grandparents in Baltimore, while Edgar and Rosalie were left in the temporary care of Mr. and Mrs. Luke Usher, the closest friends of their mother. A mere two weeks after the Poe children lost their parents—on December 26, 1811—a terrible fire at the Richmond Theater claimed the lives of seventy-two people. Just as Edgar and his siblings had been, so were many of Richmond’s children now orphaned. Though their parents were not victims of the fire, Edgar and Rosalie were taken in after the disaster by Richmond families responding to the sudden need—Rosalie by Mr. and Mrs. William Mackenzie, and Edgar by John and Frances Allan.

John Allan, a Scottish emigrant, had become a successful merchant in Richmond. He and Frances had married in 1803 but had no children of their own. The Allans took young Edgar in and had him baptized as “Edgar Allan Poe.” Though they raised him as their own child, they never formally adopted him. John Allan made for a somewhat inconsistent father, alternately spoiling and rebuking the often disobedient young boy.

Poe was a precocious child, who impressed the Allans’ friends by reading from the newspaper at the age of five, and who stood on the table in his stockinged feet at dinner parties, toasting the ladies with sweetened wine. In 1815 John Allan sailed with his wife and Edgar to Great Britain, visiting relatives in Scotland and then settling in London to open a European branch of his firm. Poe lived and attended boarding school in London until 1820, when the family returned home to Richmond. By this time, Poe was excelling in his studies, a proficient reader of Latin who also knew some French. He preferred poetry to prose and was considered a brilliant, if not overly hard-working student.

In Richmond, Poe attended schools run by a succession of Irish classicists who had the young man reading Homeric Greek as well as Virgil, Horace, and Cicero. He also began to write his own poetry. He was, by all accounts, a model student with a number of close friends. In 1824 the mother of a schoolmate, Robert Stanard, died. She had been kind to the young Poe, and he felt her passing keenly—a tragic, recurring motif in his life, which would often appear in his poems and tales.

It was shortly after this that John Allan's business partnership was dissolved and his financial situation became tenuous. Poe's relationship with his foster father began to become strained around the same time. John Allan's financial struggles, at least, were short-lived, as in 1825 he received an inheritance from his uncle worth three-quarters of a million dollars. But the wages of affection Allan was prepared to bestow on his young foster son would never satisfy Poe’s conception of what he was due. John Allan once said of him, “Edgar is wayward and impulsive...for he has genius....He will someday fill the world with his fame.” He saw the waywardness and impulsiveness of his youth but would never witness the blossoming of his genius or the fame that followed.

At the age of sixteen Poe fell in love with Sarah Elmira Royster, the daughter of one of the Allans' neighbors. They became engaged, although without the approval of their parents.

In February 1826 Poe enrolled in the one-year-old University of Virginia at Charlottesville to study ancient and modern languages. In addition to the ancient Greek and Latin he’d studied at boarding schools, he now studied French, Italian, and Spanish, and was soon fluent enough to translate in any of these languages on sight. Poe was a top student, a talented draftsman (who apparently drew caricatures of his professors, among other things), and read voraciously in various languages, particularly histories.

Poe also enjoyed some less-savory leisure activities while at university, including two strictly banned but widely practiced vices: drinking and gambling. His love of card-playing landed him in debt to the tune of $2,000, a hefty amount at the time. Upon returning home to Richmond in December 1826, he found that, not only was John Allan unwilling to cover his huge gambling debt, but Elmira Royster was now engaged to one Alexander Barrett Shelton. Her father had intercepted all but one of the letters Poe had sent Elmira during his year in Charlottesville and arranged the match with the much older Shelton.

John Allan had little understanding or sympathy for Poe's irresponsibility with money (which included other debts beside the gambling). Poe did not return to the university in 1827, and, after a serious quarrel with Allan, left home. Stopping for a short time in Baltimore, where his brother Henry lived, Poe ended up in Boston, where he worked briefly as a reporter for The Weekly Report.

On May 26, 1827, Poe enlisted in the Army as “Edgar A. Perry” and was stationed at Fort Independence in Boston Harbor. During this time, he released his first poetry collection, Tamerlane and Other Poems, published anonymously (“by a Bostonian”) with a print run of fifty copies. Not surprisingly, it received almost no attention, but contained a number of important early works, including “Tamerlane” and “The Lake.”

Poe served in the Army for two years, attaining the rank of Sergeant Major, before seeking to end his five-year enlistment early. After Poe admitted his true name and circumstance, his commanding officer would allow his discharge only if he reconciled with his foster father, John Allan. After a number of letters went unanswered, Poe returned to Richmond shortly after the death of his foster mother, Frances, just a day after her burial. John Allan finally helped secure Poe’s release from the Army and was instrumental in getting Poe an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

Discharged in April 1829, but not set to attend West Point until the summer of 1830, Poe stayed with his widowed aunt, Maria Clemm, and her eight-year-old daughter (Poe’s cousin), Virginia, in Baltimore. While there, he published his second collection of verse, Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane and Minor Poems (1829). It contained his ambitious, several-hundred-line minor opus “Al Aaraaf,” a revised and truncated version of “Tamerlane,” several other poems from his first collection, and some new poems. As he did with “Tamerlane,” Poe would, throughout his career, revise, rework, retitle, and repurpose his poems and short stories for various publications at different times. He was always refining and perfecting his work, up until the very end.

Al Aaraaf, published by the short-lived firm of Hatch and Dunning, sold few copies but did receive some encouraging critical attention. One significant bit of praise came from the noted critic John Neal, who wrote of Poe, “If the young author now before us should fulfill his destiny...he will be foremost in the rank of real poets.”

Poe entered West Point in July 1830 and again excelled academically. He also made friends, spinning tales and composing verses about them and their instructors for their amusement, as well as enjoying the local watering hole, the tavern Benny Havens.

Despite his success as a student, John Allan refused to grant Poe an allowance for what the cadet considered necessary expenses, and by January 1831, Poe proceeded to purposely get himself court-martialed and expelled from West Point for repeated absences from classes and roll calls, and disobeying orders. During this period, John Allan had taken a second wife, Louisa Patterson. The marriage and heated arguments with Poe over Allan’s past infidelities (and the bastard children who were the results) created a permanent rift between the two, and Allan finally disowned his foster son.

He left West Point for New York City in February and released a third volume, titled simply Poems. The collection featured several revised versions of earlier works, as well as six new poems, including “To Helen,” “The City in the Sea,” and “Israfel.” His fellow cadets had helped put up $170 toward its publication—and Poe dedicated the book to them—though some were disappointed Poe didn’t include some of the comic verse that had so amused them during his time at West Point. Published by Elam Bliss, the book again did little business beyond the cadets and only received one review, in the New York Mirror.

Poe returned to Baltimore in the spring of 1831, staying with his aunt Maria and cousin Virginia. His brother Henry, in poor health from tuberculosis and his heavy drinking, died at the age of twenty-four in the house of Mrs. Clemm on August 1, 1831. Henry, who was an occasionally published poet himself, had traveled around the world before the age of twenty as a crewman on the USS Macedonian. Despite being raised in separate cities, the two shared similar tastes and sensibilities, especially when it came to poetry, and were very close.

The first prose tales of Poe’s that were published came about as the result of a short story contest in the Philadelphia Saturday Courier in December 1831. Although Poe didn’t win first place, five of his stories were published in the Courier between January and December 1832—“Metzengerstein,” “The Duc de l’Omelette,” “A Tale of Jerusalem,” “A Decided Loss” (later called “Loss of Breath”), and “The Bargain Lost” (an early version of “Bon-Bon”).

In addition to the five stories published in the Courier, Poe was working on another six tales as part of a planned “Tales of the Folio Club,” which never came to fruition. The individual stories, however—“Lionizing,” “The Visionary” (now called “The Assignation”), “Shadow,” “Epimanes” (now called “Four Beasts in One; The Homo-Cameleopard”), “Silence,” and “MS. Found in a Bottle”—would all be published in various periodicals before being collected in one of Poe’s short story volumes. Poe entered “MS. Found in a Bottle,” along with several other tales from “Folio,” in a contest put on by the Baltimore Saturday Visiter and this time won the first prize of $50. The story earned Poe national attention and led to some helpful connections that would enable him to place more of his stories and gain employment as an editor.

During this time, Poe’s foster father, John Allan, had become extremely ill. Poe traveled to Richmond to call on Allan but was angrily turned away. In March he died, leaving Poe nothing. Even Allan’s illegitimate children received mentions in his will, but not the foster son in whom he saw such genius.

Through a wealthy Baltimorean named John P. Kennedy, Poe was introduced to Thomas W. White, who had begun publishing the Southern Literary Messenger out of Richmond in late 1834. Poe published his story “Berenice” in the March 1835 issue, followed by “Morella,” “Lionizing,” and “Hans Pfaall” in the next several editions. He also began to write book reviews, the severity of which were sometimes the cause of controversy. By August, Poe was employed as White’s assistant editor but within a few weeks was fired for his excessive drinking.

Returning to Baltimore, Poe hastily married his thirteen-year-old cousin Virginia in a private ceremony on September 22, 1835. He had been pursuing Eliza White, the eighteen-year-old daughter of his boss, Thomas White. It’s possible that Poe’s aunt engineered the betrothal to her daughter to “save” Poe from Eliza. Certainly, Poe had feelings for his fetching young cousin by this time—although the story is often told of how Poe used Virginia as a go-between to deliver messages to another young lady he was interested in only a couple of years earlier. But whatever the impetus, the twenty-seven-year-old Poe and thirteen-year-old Virginia were now husband and wife. Her age and their familial relations have spurred much speculation through the years on the true nature of their marital relationship. But there can be no doubt that Poe truly loved her, whether romantically or more as a sister-figure is impossible to say.

By December 1835, White welcomed Poe back to the Southern Literary Messenger, after Poe’s vow to abstain from alcohol. He would remain there through January 1837, reviewing the early work of Dickens and other authors but publishing no original fiction of his own. He did write “Maelzel’s Chess-Player” and two significant poems—“Bridal Ballad” and “To Zante”—during his tenure at the Messenger.

In the last issue Poe edited for the Messenger, he published the first installment of his only complete novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. The novel was published by Harpers in July 1938. Though it did not sell well in the U.S., it did better in England, where it was pirated, depriving Poe of any proceeds from its sales there. Poe did not think highly of his own work, later calling it “a very silly book.” The seafaring adventure, however, did apparently inspire a young Herman Melville, who wrote the considerably less silly Moby-Dick.

After leaving the Messenger, Poe and family moved to New York, where he managed to publish a couple of short stories while continuing to work on both The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym and his only dramatic piece, the unfinished tragedy Politian.

About the time that Pym was being published, the Poes moved once again, this time to Philadelphia in the summer of 1838. He struggled to find work and even considered quitting trying to earn a living as a writer. He and his wife and aunt/mother-in-law reportedly lived on bread and molasses for weeks at a time. The kindness of friends and acquaintances helped pull them through, and by the fall of 1838, Poe had been begun once again to place some new stories in the new Baltimore American Museum.

Over the next few years, Poe would continue to sporadically publish stories, poems, and reviews. In 1839 Lea and Blanchard brought out Poe’s collected Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque in two volumes. The 750 copies sold slowly, but it did receive a good review in Godey’s Lady’s Book, a popular magazine at the time. In the same year, he became coeditor, with the owner, of Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, where he published a number of stories, including “The Fall of the House of Usher.” A year later he was once again discharged for drunkenness and arguing with his employer, William E. Burton (although the two reconciled soon after).

Burton sold his magazine in the fall of 1840 to George Rex Graham, who folded it into his magazine Casket to form Graham’s Magazine. Burton recommended Poe to Graham, and the author began a fruitful tenure as editor of Graham’s. Between December 1840 and January 1843, Poe published eight of his most-loved short stories, including “The Masque of the Red Death” and “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” regarded almost universally as the first true detective story—and certainly the direct ancestor of all that have followed in the genre. He also published one of his best-known poems in Graham’s, “The Conqueror Worm.”

In January 1842 Virginia displayed the first signs of tuberculosis—a sad, recurring family tradition. While playing the piano and singing, she started to cough up blood—what Poe described later as a burst blood vessel in her throat, but was actually a symptom of the disease that would render her invalid for much of the next five years. Poe began to drink more heavily under the strain and suffered a brief illness that spring. When he returned to work, he found that his fellow editor at Graham’s had taken over. Poe quit Graham’s and continued to submit tales, sketches, and some verse to other magazines while trying to secure an appointment to the Customs House in Philadelphia through a friend who knew President Tyler’s son. That fell through, possibly due to Poe’s drinking. Poe also tried, unsuccessfully, to start up a literary journal, The Stylus, in partnership with Thomas Cottrell Clarke, to be illustrated by Felix O.C. Darley.

Despite Poe’s financial struggles and personal setbacks, he wrote some of his most affecting and memorable stories and poems over the next few years. “The Pit and the Pendulum” debuted just before Christmas 1842, followed shortly thereafter by “The Tell-Tale Heart” in January 1843. Poe submitted his story, “The Gold-Bug,” for a contest by the Dollar Newspaper and won the prize of $100. Published in June 1843, it brought Poe his first taste of national acclaim. It was reprinted widely and was even adapted for the stage at the American Theatre in Philadelphia—the only such dramatization produced during Poe’s lifetime.

Poe published only one poem in 1844, “Dream-Land,” but was busy churning out short tales and sketches, including his “Balloon-Hoax,” “The Premature Burial,” and his third detective story featuring C. Auguste Dupin (after “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” and “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt”), “The Purloined Letter.” By this time Poe, Virginia, her mother, and their black cat Catterina (or Kate) had moved to New York, where Poe joined the staff of the new Evening Mirror, as an editor. They were soon settled into the farmhouse of Mr. and Mrs. Patrick Henry Brennan, near what is now 84th Street and Broadway, close to the Hudson and a large rock called “Mount Tom” that overlooked the river. Poe and Virginia enjoyed sitting on it and gazing across the then-rural riverland north of the city. It was in the Brennans’ farmhouse that Poe put the final touches on the poem that would vault him to worldwide fame and with which his name would become synonymous.

Poe first offered “The Raven” to Graham’s, who rejected it. But the poem was soon accepted by George Hooker Colton for his new magazine, the American Review. On January 29, 1845, the Evening Mirror published copies of advance sheets printed for the February issue of Colton’s American Review, accompanied by an enthusiastic introduction by the Mirror’s publisher, Nathaniel P. Willis, and revealing the author’s name (“The Raven” would appear in the Review under the byline “Quarles”). The reception was immediate and overwhelming, making Poe a household name almost overnight. “The Raven” was copied, parodied, and even anthologized in a textbook within a matter of weeks. Although the poem did not earn him much initially (nine dollars upon publication), it did bring the kind of fame that allowed Poe a multitude of opportunities.

Soon after publication of “The Raven,” Poe gave a lecture at the New York Society Library, in which he praised the poems of Frances Sargent Osgood. Though she didn’t attend, she soon managed to meet Poe, and a platonic romance ensued, carried out in part with an exchange of complimentary poems. Frances seemed to have a good influence on Poe, and Virginia even seemed to encourage their friendship.

Poe was editing the Broadway Journal beginning in January 1845 and by October purchased the paper with help from Horace Greeley and others. The Journal lost money, however, and was forced to shut down, publishing its final issue on January 3, 1846.

The Poe family moved to a modest rented cottage in Fordham, further north of the city in what is now the borough of the Bronx, near the newly founded St. John’s college (now Fordham University). Poe later idealized the small house in his final published story, “Landor’s Cottage.” As Virginia’s health grew worse, a family friend, Mary Louise Shew, was brought in to help Mrs. Clemm nurse her daughter. On January 30, 1847, Virginia Poe died after a five-year struggle with tuberculosis. She was twenty-four years old. Poe fell ill himself following Virginia’s death and was nursed by his aunt and Mrs. Shew. He published very little prose that year and one major poem, “Ulalume.” He was working on a long treatise on cosmology, delivered as a lecture called “The Universe” at the New York Society Library in February 1848 and expanded into a book titled Eureka, published by Putnam in July 1848. Although a little-known work with a small, five-hundred-copy print run, Poe thought highly of it, enough to say in a letter to his aunt, “I have no desire to live since I have done Eureka. I could accomplish nothing more.”

Poe continued to lecture and give readings of his poetry in New York, Richmond, Baltimore, Providence, and Boston. Ever the romantic, he pursued, and was pursued by, a number of ladies in several of the cities he visited. When the poet Sarah Helen Whitman sent a poem, “To Edgar A. Poe,” to be read at a Valentine’s Day Party of a friend’s in New York, Poe heard of it and composed a reply, “To Helen [Whitman].” After more romantic correspondence, Poe finally met the young widow at her home in Providence. Helen was fascinated by transcendentalism and the occult, dressed eccentrically, and loved Poe’s poetry and prose. Poe fell in love instantly and proposed marriage soon after meeting her. She accepted, although with reservations due to his drinking, and took the precaution of transferring her property over to her mother and sister. Within a month, the engagement was off, though Helen would always retain a high opinion of Poe.

The last year of Poe’s life was active, despite worsening health and increased heavy drinking. He published several stories, including the wicked revenge tale, “Hop-Frog,” and some of his greatest poems, including “Eldorado,” “For Annie,” “The Bells,” and “Annabel Lee,” the poem Poe was convinced would be his last.

Poe spent a few happy months in Richmond, where he visited with his sister Rosalie and many childhood friends. He even called on his onetime fiancée, Elmira Royster Shelton, by this time a widow. Poe once again proposed marriage and was accepted, though her school-aged children did not approve and vetoed the match.

Poe left Richmond for Baltimore in late September and reportedly began to drink again. He was found by Joseph W. Walker on October 3 on Lombard Street in Baltimore, extremely ill and disoriented. Walker summoned a doctor, who took the author by carriage to Washington Medical College. Unconscious or delirious for most of the next few days, Poe died early in the morning of Sunday, October 7, 1849. No definitive cause was ever found for his death. “Congestion of the brain,” a common euphemism for death from alcoholism, was the reason given by the October 9 Baltimore Clipper.

Most of the obituaries were kind, but for one that painted Poe as a brilliant artist but despicable human being, written by the editor and critic Rufus Wilmot Griswold in the New York Tribune, and signed “Ludwig.” It began: “Edgar Allan Poe is dead....This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it....he had few or no friends.” It would become an unfortunate irony that Griswold, an acquaintance of Poe’s who collected a few of his poems for an 1842 anthology, would soon take on a critical role in shaping Poe’s literary legacy. When Maria Clemm, Poe’s aunt, asserted control of his estate (he died intestate), she, for reasons unknown, asked Griswold to become Poe’s literary executor. Within six weeks of the author’s passing, Griswold gathered together the first two volumes of The Works of the Late Edgar Allan Poe, collecting his poems and many of his tales, which were published in January 1850.

For the third volume, which appeared in late 1850, Griswold prepared a biographical sketch, entitled “A Memoir of the Author,” which painted Poe as a depraved, cynical, and drug-addicted lunatic. Griswold forged letters, passed along half-truths, and twisted the facts to suit his personal view of Poe. The Works sold, and Griswold’s distortion of Poe’s life became part of the author’s mystique. In his attempt to assassinate Poe’s character, Griswold may have created a more irresistible portrait of the artist, particularly one whose works so often revealed the ghastly and grotesque corners of the human psyche.

Subsequent biographies and anthologies have corrected Griswold’s posthumous libel, and over the course of more than a century and a half, Poe’s tales, poems, and sketches have earned the author untold legions of devoted fans. Poe influenced writers from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, H.G. Wells, and Jules Verne to Ray Bradbury and Stephen King; Charles Beaudelaire’s translations of his work made him more famous in Europe than in America for a time; societies, museums, and landmarks to Poe exist from Baltimore and Richmond to Philadelphia, Boston, and New York; and the highest honor an American mystery author can receive is the Edgar, named in honor of Poe by the Mystery Writers of America. The admiration and success that largely escaped Poe during his short and often unhappy life came in ever-mounting waves after his death. The works, after all, speak for themselves.